Could you give us a brief overview of how you and Pat McCluskey came to found ANCA in 1974?

Could you give us a brief overview of how you and Pat McCluskey came to found ANCA in 1974?

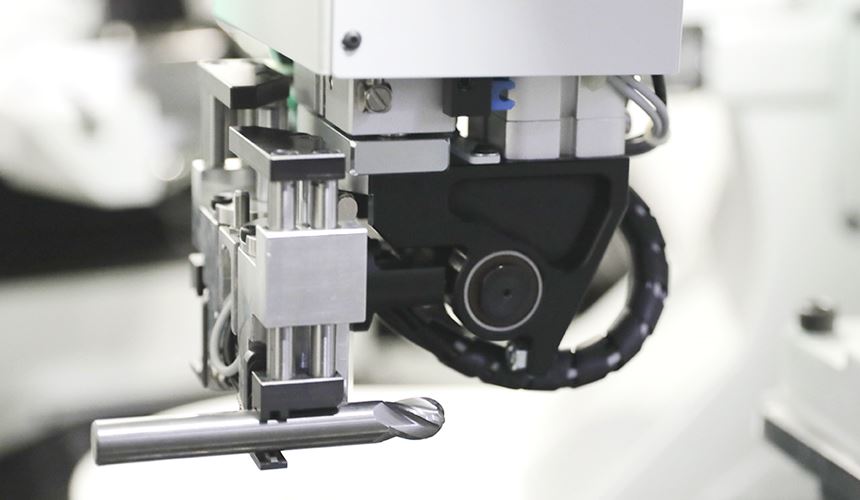

We were working with minicomputers at the time and got the idea of modifying them to direct simple operations on the NC machine tools that were then available, effectively developing early versions of today’s CNC machines. We quickly realized that Australia, where we are headquartered, wasn’t the most productive place to market this technology, so we were lucky to have a colleague in the United States who introduced us to machine tool OEMs who incorporated the controllers we were developing into their cutter/grinder machines in Indianapolis. This was in the early eighties, and by then we’d realized we wanted an end user product of our own, so we designed and manufactured a CNC cutter/grinder prototype that we took to IMTS in 1986. We sold that machine, learned out lessons from the experience, and began improving our product. We felt like our concept was sound, designing software to measure grinding cutting tools in process, if we could only streamline the technology and find the right markets.

So the U.S. was your first target market? How did things evolve from there, in terms of your distribution model in North America and around the world.

Yes, we definitely targeted the States initially, and we tried distributors and sales representatives at first, but that approach just didn’t seem right for us, or for them. So we decided to establish ANCA subsidiaries throughout the U.S. based on our existing location in Detroit, Michigan. That allowed us to build our strength and reputation, eventually spreading into areas around the world, including Europe, the U.K., Germany, China, Asia, and elsewhere. Primary manufacturing still takes place in Melbourne, Australia, but we also have facilities in Thailand and Taiwan.

Could you name some technological milestones along the way that have been particularly important to ANCA’s success?

I would have to say that in-machine probing of grinding cutting tools was one of our first big game-changers. We really led the way in the area. And then, in 1991, when we began developing 5-axis controls that synched with robotics, the industry really took notice. It was an acknowledgment that machining systems and technologies were starting to merge, and that it was important to start thinking about them holistically instead of just as component and separate processes. Then I’d say 3D simulation of the complex geometries of various cutting tools brought design forward lightyears into the future, as did the shift from ball screws to tubular linear motors in terms of increasing both accuracy and machine life. When you add to that servo-drives that monitor and control internal machine temperatures, long-term machine stability is increased significantly.

Looking back to those early years when you and your partner invested $4,000 on a minicomputer to get this whole enterprise off the ground, what surprises you the most?

Looking back to those early years when you and your partner invested $4,000 on a minicomputer to get this whole enterprise off the ground, what surprises you the most?

I suppose that ANCA is now a thriving business with more than 1,000 employees, and that we’re now a well-known manufacturer of CNC grinding machines, motion controls and sheet metal solutions around the world. We’ve managed to maintain our roots here in Melbourne, where it all started, even though we export 99-percent of our products to customers in 45 countries around the world. I think that’s a pretty interesting business model, and one that neither Pat nor I could’ve imagined back when we first got started down this path.