Win By Losing

If you’re looking to shed a few extra pounds, gain lean muscle and boost energy levels, there’s a plethora of trendy diets to choose from including, but not limited to, Atkins, Keto, Weight Watchers, Whole 30, Paleo, Intermittent Fasting, and Tom Brady’s Diet.

Similarly, a growing trend among many proactive job shops is to create a slimmer, more efficient storeroom. Much like diets, a lean system is designed to melt away excess fat and make your operations faster, flexible, and more competitive. The Toyota-developed system for delighting the customer and enhancing the long-term profitability of the firm has earned a reputation for revolutionizing a wide variety of industries. Successful adopters have demonstrated it’s much more than a manufacturing system: it’s also an overall operational excellence system. And it’s accomplished with the participation of all employees focused on maximizing value to the customer through the relentless elimination of waste. Whether the waste is excess production resources, transportation, or extra inventory, lean is all about doing more with less. When done right, the results are lower costs, better quality, and shorter lead times.

A common misconception is lean manufacturing principles and practices are mostly applicable to high volume, low mix manufacturing like Toyota. This is not the case when judicially applied as we’ll see in this article. Job shops are predominantly make-to-order (MTO) and/or engineer-to-order (ETO) production environments. They may produce dozens if not hundreds of different products (although they’re all somewhat similar) versus two to six in a high-volume assembly plant like Toyota (which is mostly make-to-stock [MTS]). The demand for the various products may vary significantly but are relatively small in comparison to the high production facilities. The impact on the storeroom dictates stocking a large assortment of parts in much smaller quantities. Therefore the layout must be designed with a high degree of flexibility.

Your Bill of “Rights”!

Your Bill of “Rights”!

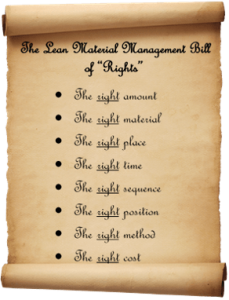

Before proceeding, let’s address a fundamental question: What is the mission of a lean material management system? It’s to supply the right amount of the right material at the right place at the right time in the right sequence in the right position using the right method and at the right cost. The function of the storeroom then is to support this mission by buffering incoming material (e.g. raw material, purchased parts, Work in Process [WIP], Maintenance Repair and Overhaul [MRO], etc.) from suppliers (both external and internal) and outbound delivery to work centers within the shop. This means achieving high customer service — with appropriately sized inventory levels — being responsive to changes in demand, and keeping costs as low as possible. Creating a lean layout will serve as a cornerstone for achieving this purpose.

1. Recruit a Winning Team

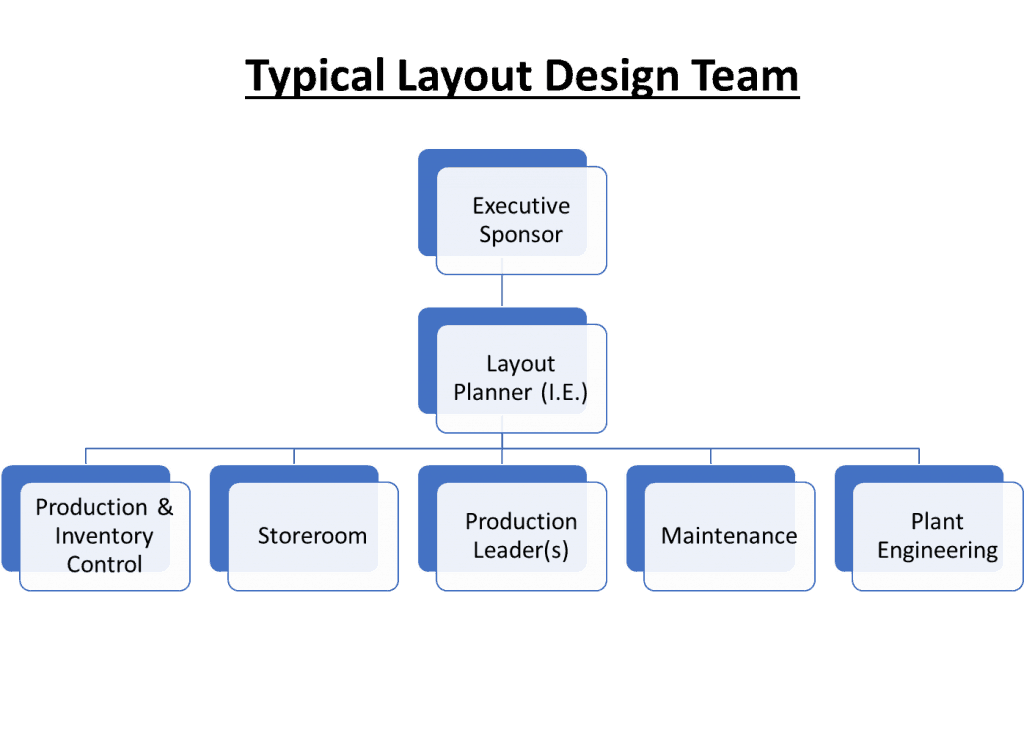

Football fans understand the importance of building a well-rounded team. For example, if the only talent on the team is the quarterback, whereas the blockers, running backs, receivers and coaches are mediocre, the chances of being victorious on the gridiron are slim to none. Similarly, for a storeroom layout redesign project to be successful, it’s also important to recruit a well-rounded team that spans the organization both horizontally and vertically. Many areas are affected, especially when determining the proper location for the storeroom. The typical team members are production and inventory control, storeroom leader, select team leaders from the shop floor, representatives from maintenance, plant/manufacturing engineering, shipping and receiving. Keep in mind it’s not uncommon in a job shop environment for one person to wear multiple hats. Implementing the revamped storeroom layout will go more smoothly if you encourage employee suggestions and address them in the plan.

The “team captain” should be a senior level industrial engineer who has the knowledge skills and experience in layout design, lean principles and project management. It’s been my experience that few job shops employ real industrial engineers let alone someone with this level of talent. The layout planning in the job shop is a highly intermittent type of activity. It usually falls under special projects. Internal engineering resources are not used to it as part of their regular daily activities and often results in a haphazard layout. Thus, it often behooves leadership to bolster this role with an outside expert in the field. Leveraging an outside independent professional can help overcome some lack of objectivity and imagination (can’t see the forest for the trees), or some political or emotional agendas common in organizations.

The “team captain” should be a senior level industrial engineer who has the knowledge skills and experience in layout design, lean principles and project management. It’s been my experience that few job shops employ real industrial engineers let alone someone with this level of talent. The layout planning in the job shop is a highly intermittent type of activity. It usually falls under special projects. Internal engineering resources are not used to it as part of their regular daily activities and often results in a haphazard layout. Thus, it often behooves leadership to bolster this role with an outside expert in the field. Leveraging an outside independent professional can help overcome some lack of objectivity and imagination (can’t see the forest for the trees), or some political or emotional agendas common in organizations.

In addition, the top boss needs to be personally involved to “put some skin in the game.” Top management will be most familiar with the big picture of the business including long-range strategies, new product offerings, future programs and sales trends. They write the checks and will be the ones to approve and acquire the needed resources for implementation.

Don’t hesitate to bring into the fold subject matter experts on an as needed basis. For example, put the bean counters into the game when it’s time for establishing project budgets and conducting financial justification.

It’s best to limit the team size to not more than 10 members in order for it to be manageable and keep things on track. For small and medium size companies six to eight players will usually suffice. Figure 2 shows an example of a typical layout design team.

Early in my Industrial Engineering career I was involved in a layout redesign project for an automotive supplier. The company I worked for at the time was a subconsultant to a larger prime consulting firm. For various reasons we were given restricted access to the client’s personnel, especially those intimately involved and knowledgeable in the day-to-day operations. Consequently, the operations folks always referred to the new layout proposals as “Jeff’s layouts”. At the end of the day, the redesigned layout never made it off the drawing board. Lesson learned: don’t begin the layout process until you’ve recruited a winning team. Active involvement and participation from a cross-functional multilevel team is not an option: rather it’s essential for project success. A total team effort will not only result in a better layout solution, but also will cultivate organizational-wide “buy-in” when it comes to implementing the new layout because the employees will take ownership of the plan they helped to develop.

2. Be S.M.A.R.T. About It

2. Be S.M.A.R.T. About It

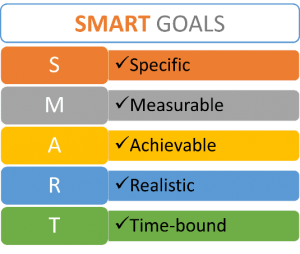

It can be tempting to dive into the CAD development work right out of the gate. Don’t fall into that trap. Keep in mind the eventual layout must meet and achieve your unique goals to be fully purposeful. What should be your goals? You should always aspire to make your goals SMART by ensuring they are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-bound. So instead of using vague catchphrases like “streamline material flow”, specify SMART goals such as “reduce material pick times by 30% within the next six months”. These goals will provide a framework for making difficult trade-offs when evaluating alternative plans. They will also serve as a yardstick for how well the implemented layout achieves the intended performance improvement targets.

Think long range when defining goals for the new layout. For example, what are your projected sales volumes over the next five years? What products are phasing out and what new ones will be introduced? How much space do you need now and in the foreseeable future? These vary for each situation, but hammering them out upfront in the planning process is needed in order to make sound plans.

3. Get with the (5S) Program

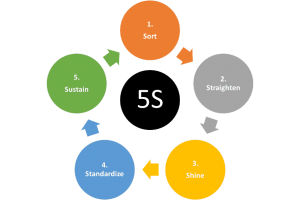

One of the common perceptions I often encounter is the “lack of floorspace” available for a new layout. And sure enough I often see aisles cluttered with pallets, defective and obsolete inventory crammed into corners, barbecue grills and broken office furniture stuffed into pallet racks. In reality it’s the disorganization and clutter that results in wasted space. The real focus should be on more effective use of the existing real estate. This is where the lean method 5S shines (pun intended). If you haven’t initiated a 5S program yet, there’s no better time to start than when embarking on your layout rearrangement endeavor. 5S is one of the fundamental tools in lean manufacturing, used to create and maintain a clean, organized and safe workplace. Some companies erroneously treat 5S as nothing more than glorified version of housekeeping. In reality ‘housekeeping’ is only a small part of the program. 5S is a powerful process for workplace performance improvement where there’s “a place for everything and everything in its place.” And not surprisingly it’s called 5S because it consists of 5 components and each word starts with a Letter S as shown in figure 4.

I worked with a company whose factory was splitting at the seams. Material was crammed into every nook and cranny, containers clogged aisles, and they even used a semi-trailer for extra material and “stuff” storage. Furthermore, they projected a 50% increase in growth over the next several years so additional workcells were required to handle the anticipated rise in throughput. They initiated the 5S activities to free up a significant chunk of real estate inside the shop that was desperately needed for a new central storeroom and the additional workcells. That, combined with a comprehensive layout redesign and optimization effort, enabled them to implement the new central storeroom including a new kitting process and increase throughput capacity by 50% without having to relocate their operations or expand beyond their existing four walls. And yes, the truck trailer was no longer needed for storage.

I worked with a company whose factory was splitting at the seams. Material was crammed into every nook and cranny, containers clogged aisles, and they even used a semi-trailer for extra material and “stuff” storage. Furthermore, they projected a 50% increase in growth over the next several years so additional workcells were required to handle the anticipated rise in throughput. They initiated the 5S activities to free up a significant chunk of real estate inside the shop that was desperately needed for a new central storeroom and the additional workcells. That, combined with a comprehensive layout redesign and optimization effort, enabled them to implement the new central storeroom including a new kitting process and increase throughput capacity by 50% without having to relocate their operations or expand beyond their existing four walls. And yes, the truck trailer was no longer needed for storage.

So, unless you have an ongoing vigorous 5S type program in place, you may be pleasantly surprised at how much prime property is lurking inside your four walls.

4. “Stay in Stock”

Zero inventory is not a realistic goal. Insufficient inventory will lower productivity and on-time delivery performance. Instead supplying the point of use with the correct amount of material to meet production at the lowest possible cost is the aim. The storeroom supports this objective by providing a buffer to decouple fluctuations between inbound material supply and outbound demand and to accommodate batching. Fluctuations are the unplanned deviations that occur in the material flow pipeline such as late/early supplier deliveries, over/under shipments, quality defects, machine and equipment breakdowns, worker absenteeism, changes in customer orders, etc.

Batching is influenced by minimum order quantities, economic order quantities (economic lot sizes), machine and equipment changeover costs, volume discounts, etc. For example, if you’re consuming an average of twenty M10 bolts per day, you’re not going to order that many each day. Instead, you might order a box of 200 every two weeks. Reducing both process variation and batching provides opportunities to reduce the storeroom inventory. Decreasing the amount of inventory in the storeroom is key to reducing floor space requirements and inventory handling / carrying costs.

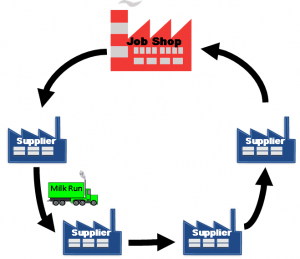

An effective tactic to reduce inventory for purchased parts is having more frequent shipments. A lean approach to increasing shipping frequency without taking a big hit on transportation costs is to employ milk runs. The concept is similar to when a truck collects milk from the different farms and brings it to the processing facility. Instead of receiving a big shipment of a single item from a particular supplier, milk runs enable a dedicated driver to combine less-than-truckload (LTL) shipments into a single trailer from multiple suppliers, on a predetermined route at scheduled pick-up times. This necessitates that suppliers are in close proximity to each other or along the same route. Also, it works best if you have sufficient and stable throughput volumes to support the process. If you’re dealing with customer order sizes of mostly onesies and twosies, then this approach wouldn’t make sense for your environment. Smaller companies will often outsource this service to a third-party logistics provider (3PL) who can provide the benefits of milk runs for multiple customers. The transportation cost of shipping on a regular and timed loop will usually be lower than LTL or parcel delivery.

An effective tactic to reduce inventory for purchased parts is having more frequent shipments. A lean approach to increasing shipping frequency without taking a big hit on transportation costs is to employ milk runs. The concept is similar to when a truck collects milk from the different farms and brings it to the processing facility. Instead of receiving a big shipment of a single item from a particular supplier, milk runs enable a dedicated driver to combine less-than-truckload (LTL) shipments into a single trailer from multiple suppliers, on a predetermined route at scheduled pick-up times. This necessitates that suppliers are in close proximity to each other or along the same route. Also, it works best if you have sufficient and stable throughput volumes to support the process. If you’re dealing with customer order sizes of mostly onesies and twosies, then this approach wouldn’t make sense for your environment. Smaller companies will often outsource this service to a third-party logistics provider (3PL) who can provide the benefits of milk runs for multiple customers. The transportation cost of shipping on a regular and timed loop will usually be lower than LTL or parcel delivery.

If you manufacture any MTS items in-house, then you probably have opportunities to reduce inventory by decreasing production lot sizes. A proven lean technique to enable smaller productions runs is called setup time reduction (also known as Single Minute Exchange of Die [SMED]). It’s a systematic method of reducing the amount of time needed to changeover a process from the last item for the previous lot to the first good item for the next lot. In many cases, this system can reduce setup times from hours to minutes with minimal capital investment.

To calculate maximum inventory level for each part to be stored, create a part planning spreadsheet with the formula:

- For purchased parts:

Maximum inventory level = planned order quantity + target safety stock - For in-house produced parts:

Maximum inventory level = planned lot size + target safety stock

Let’s assume we receive weekly shipments containing 50 units of a particular purchased part and safety stock was 7 units, then maximum inventory level = 50 +7 = 57 units. To determine safety stock, you need to consider variables such as suppliers on-time performance and quality, risk of bad weather and delays at customs, variations in demand, machine and equipment downtime, etc.

Now add a column to your spreadsheet for container density (i.e. standard quantity per container) and calculate the maximum number of containers to store by dividing maximum inventory level by the container density. If, for example, the standard container quantity is 10 units, then the storeroom must be able to hold six containers (⌈57 ÷ 10⌉) for our example part.

Finally, we can add columns to our spreadsheet for container dimensions and figure out the size and quantities of storage shelves, racks and drawers.

By systematically analyzing your data, engaging your workforce and applying appropriate lean tools, you can significantly downsize inventory levels (and free up valuable floor space) without adversely impacting chances of a stock out.

5. Be Prepared for a Flash Flood

What happens when overages are introduced such as a supplier over-ships or delivers earlier than scheduled? Or perhaps fewer parts are consumed than planned? Or there’s an engineering specification error? When planning your layout, remember to designate space for an overflow area near the storeroom to hold this excess inventory. It should be in a conspicuous location so to draw attention to the issue and so the root cause can be remedied in a timely fashion.

Summary

This article covered the preliminary vital steps for designing a lean storeroom layout. Although no layout has been developed at this stage of the game, we’re setting the groundwork for ultimate project success. In part 2 we’ll delve into layout design strategies including how to integrate your storeroom layout with the overall master layout plan, developing detail plans, kitting approaches, and equipment selection criteria.

Have a question about industrial and systems engineering services offered by PES? Send me your question by clicking this link http://pessolutions.com/contact/ and I’ll get you the answer!