Jack works as the primary data analyst across multiple research activities. His expertise lies in data modelling, economic forecasting and streamlining processes to enhance product efficiency. Jack is responsible for the upkeep and enrichment of our MIO tracker.

The manufacturing economies of the G7 group of nations face growing competition from the rest of the world, as globalization connects countries’ economic fortunes more closely. Huge changes have taken place within manufacturing as companies – particularly within the industrialized nations – turn to automation to tackle growing problems with skills and labor shortages and rising input costs, coupled with demand for greater efficiency and throughput. In addition, world events resonate within industry and the impact of global conflicts on energy costs and supply chains are affecting production.

Meanwhile, many of the BRICS nations have improved production capacity and output growth, as domestic demand increases. In the current climate, opportunities may exist for the BRICS economies to capitalize on weaker projected growth for the G7 nations and expand their manufacturing industries due to costlier exports and already strong production capacity. This begs the question, can the BRICS nations take advantage of the current slump in manufacturing output in the G7, and will they choose to do so?

In existence since 1973, the G7 is a political and economic forum of industrialized nations (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, with the European Union as a non-enumerated member). Formed much more recently, the BRICS geopolitical bloc comprises Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates. As a whole, the BRICS nations have traditionally had lower production capacity than the G7 countries.

According to the latest data from Interact Analysis’ quarterly Manufacturing Output Tracker (MIO), 2024 will prove tough for manufacturing worldwide. Despite lower output being forecast for most nations, the dip for many will be relatively low. When China is excluded from the global data, production output is expected to drop to -0.9%. China, the ‘Factory of the World’ continues to prop up the figures, with the forecast at 0.6% when it is included in the data.

Manufacturing conditions remain difficult for the G7

Germany’s manufacturing industry has been the worst hit of the G7 nations as it attempts to shift its reliance on Russian gas, experiences falling business from China, and is undercut by cheaper production elsewhere. The overly bureaucratic industrial and political system continues to hamper recovery. Taking the German car industry as an example, Volkswagen recently announced plans to close two of its production facilities in its home country. And it is not the only major automotive company to do so, with others considering plant closures, including tyre giants Continental and Michelin. Ford has revealed it is cutting 3,500 jobs at a German plant, and Automotive Cells Company (ACC) has halted construction on battery manufacturing sites in both Germany and Italy.

Italy has seen minor effects of the global slowdown, but the severe problems in Germany have not manifested as acutely as feared, with machinery sales remaining robust. However, growth has flatlined and the current situation is wait and see. High production costs and production capacity in many large European economies mean they have struggled to increase production. Both Germany and Italy have witnessed companies moving factories to cheaper neighboring countries like Romania, Czechia, Hungary and Poland. The effect of this movement within the European Union benefits the wider G7 to some degree, but is to the detriment of individual G7 members.

We have yet to see any impact of France hosting the 2024 Olympic Games show within the manufacturing data, so it is unclear what effect, if any, the event will have on the nation’s economic fortune. Meanwhile, the UK continues to feel the aftershocks of Brexit, with import and export costs increasing. As the economy falters, it remains unclear whether a change of government will bring about changes in relations with the rest of Europe and policies that affect manufacturing.

Japan is the third largest manufacturing economy in the world, but it continues to struggle as the accelerating decline of the yen places households under pressure. As a net importer, the pressure on internal consumption is coupled with emerging southeast Asian economies undercutting it in some of its key manufacturing sectors.

Within the G7, the US is not experiencing economic pressures to the same extent and consumer demand has remained robust, despite rising prices. The Interact Analysis MIO Tracker is not currently forecasting a contraction for US output in 2024. Additionally, US industry has benefitted from government policies such as the CHIPS and Science Act. The US has invested heavily into the growing semiconductor industry to secure domestic production and reduce imports from China. This stimulus will likely continue to boost manufacturing in the US. With less proactive measures from the government, Canada’s manufacturing data is weaker, affected by a dip in global demand for metals. The latest drop has increased calls for action to boost production.

What does this mean for the BRICS economies?

With the current downturn largely affecting the Americas and Europe in particular, the BRICS economies have shown greater resilience. Despite China’s weak recovery in domestic demand, due to its fluctuating housing market, it is still expected to increase production output by +2.3% in 2024 as exports rebound. So far, the government has avoided large-scale economic stimuli, although reports now suggest that some form of stimulus is being planned. The real estate market is expected to stabilize in 2025, while higher rates of growth are predicted for production output into 2026 and 2027.

India has been particularly resilient and is on a strong growth path. Its high population density and poor availability of raw materials mean it is unlikely to become the ‘next China’. However, Interact Analysis has raised India’s long term growth forecast to +5.4%. India is capitalizing on weaknesses in the G7 through its manufacturing industry as it continues to trade widely with, for example, China, Russia and the US. A significant increase in investment is also being hailed as a key driver of growth. S&P Global has predicted it could rise to become the third largest economy in the world by 2030. It may well be that the Indian government’s ‘Make in India’ flagship program is starting to bear fruit. However, it is notable that India’s manufacturing industry is facing some challenges within certain sectors from smaller countries, particularly in areas such as semiconductor manufacturing from territories such as South Korea and Malaysia.

The overall picture is inconsistent across the manufacturing industries of all the BRICS nations. For example, according to the MIO, the Covid-19 pandemic affected Brazil more than any other large manufacturing economy and it is still regaining lost ground following a particularly difficult 2023. Brazil is not expected to see manufacturing growth return until at least 2025 and it remains heavily reliant on exports to China and the US, both of which have dipped. However, it is anticipated that monetary policy changes will return its economy to growth and boost manufacturing.

Russia’s economy has generally held up, despite the war in Ukraine, and it has spent heavily on military production. But it is not clear how long this will last. Additionally, some of the smaller BRICS economies, such as Ethiopia, South Africa and Egypt, have experienced a range of political and economic challenges that have affected manufacturing productivity. The UAE in contrast has seen diversification policies and increases in oil prices and production boost its output and economy.

So, can and will the BRICS economies capitalize on the current G7 manufacturing slump?

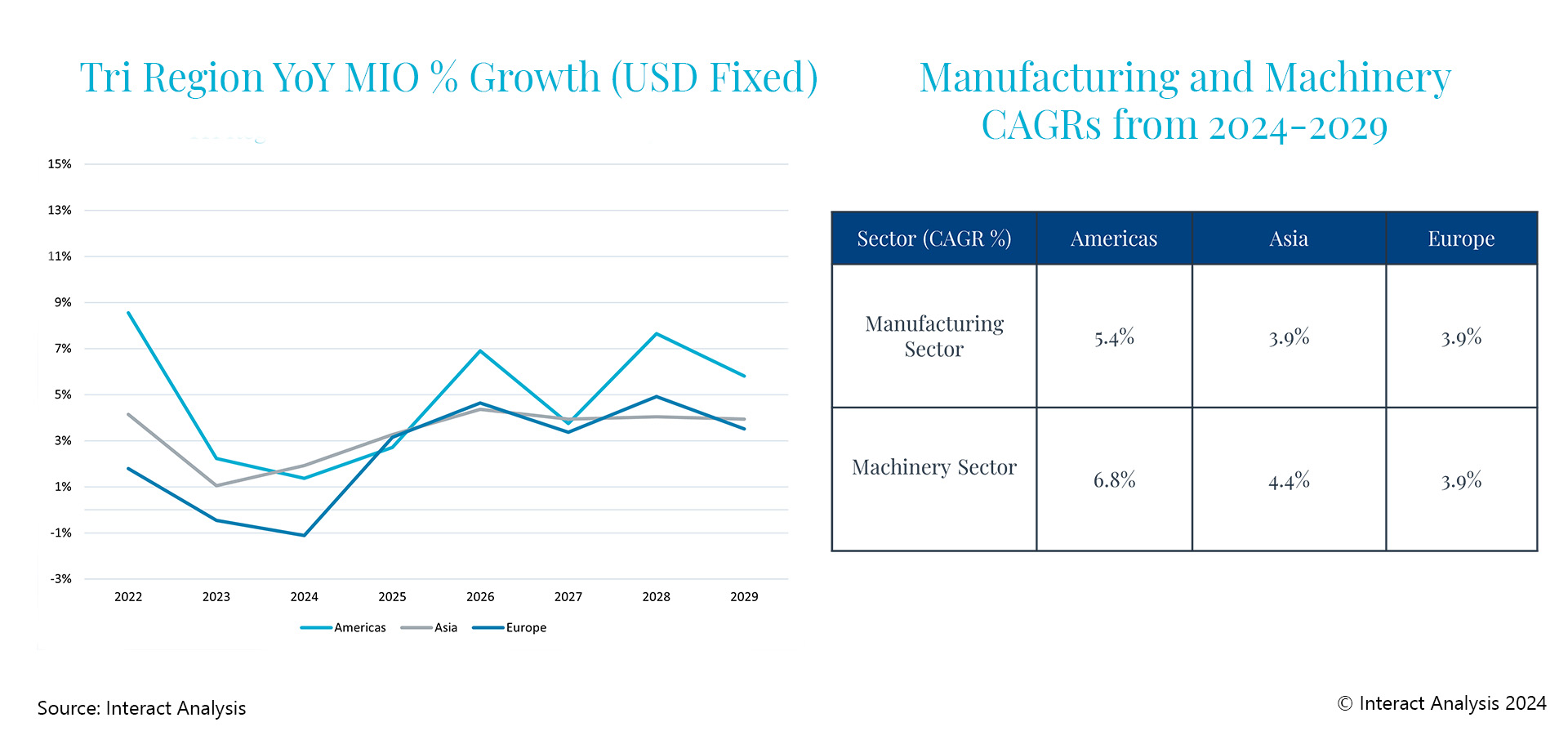

Any capital BRICS nations are going to make from the current downturn will need to be swift, as another manufacturing downturn is not forecast by Interact Analysis until 2029 or 2030. Looking at the MIO Tracker, the Americas is forecast to see a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.4% between 2024 and 2029, considerably higher than the 3.9% anticipated for Europe and Asia. Asia’s lower 5-year CAGR is mostly due to the sheer size of China’s manufacturing industry, as it is harder to achieve growth from a larger base. India’s manufacturing CAGR for the 5-year period is 6% and Asia as whole – excluding China – is 5.5%.

Growth trajectories are predicted for the 3 major manufacturing regions

There is little time for the BRICS nations to capitalize on the widespread manufacturing struggles of many of the G7, so it is unlikely that much additional growth will be generated in the short term. The post-Covid nearshoring trend is continuing and government incentives to generate domestic investment (such as the CHIPS Act in the US and Make in India) may become more widespread. With the G7 undoubtedly facing increasing competition from the rest of the world, this may be a means by which wealthier countries attempt to protect their manufacturing industries and reduce over-reliance on Chinese imports. However, China is such a dominant force in global manufacturing, with all the benefits that rich natural resources and domestic consumption bring, that it is unlikely to see any significant impact in the near term.

The picture is also far more complicated than simply G7 vs BRICS nations. We have seen smaller, more agile nations such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Czechia and Poland grow their manufacturing industries and specialized industries as larger territories experience output struggles. With such a wide range of variables in place and an imminent global recovery forecast, it appears that the BRICS nations are unlikely to make manufacturing capital out of the current downturn in many of the G7 economies.

By Jack Loughney, Senior Research Analyst – Interact Analysis